Mental & Social Health

Even as our visibility and social acceptance grows, our communities still face serious social and health disadvantages as we exist in societies that prioritize straight and cis populations. We are more vulnerable to not only HIV and STIs, but also mental health disorders, challenges with substance use, social isolation, depression and suicide, to name just a few.

Research has shown that many of these challenges are not the result of who we are, or our own choices. They come from social conditions that systematically harm our communities. These could be things like violence directed toward us as queer and non-binary, trans, Two-Spirit people as well as broader issues like most of us struggling to get access to affirming health care that respects our identities and/or sexual activities)

When we think about things like discrimination and social conditions, we see that those of us who are trans, racialized, disabled, or members of marginalized groups are even more likely to face barriers and health inequities.

Knowing that we are not the problem and understanding the specific ways our social and mental health is shaped by living in a heterosexist and cis-centric world can be empowering and help us begin to work on our social and mental wellbeing.

For a more information about mental health, queer men, and non-binary people, as well as customized resources and programs to help you cope, check out HIM’s Take Time for Your Mind.

Social Conditions and Our Health

What comes to mind when you think of health?

Many of us are taught health just means whether a person has an illness or disease. However, health goes beyond that and means the state of a person’s physical, mental and social well-being. A person’s health and wellbeing is shaped by a lot of factors. While some of these can include genetics and lifestyle we’re starting to understand the complicated ways in which the world around us can shape our health and wellbeing. For example, many people smoke as a way of coping with stress.

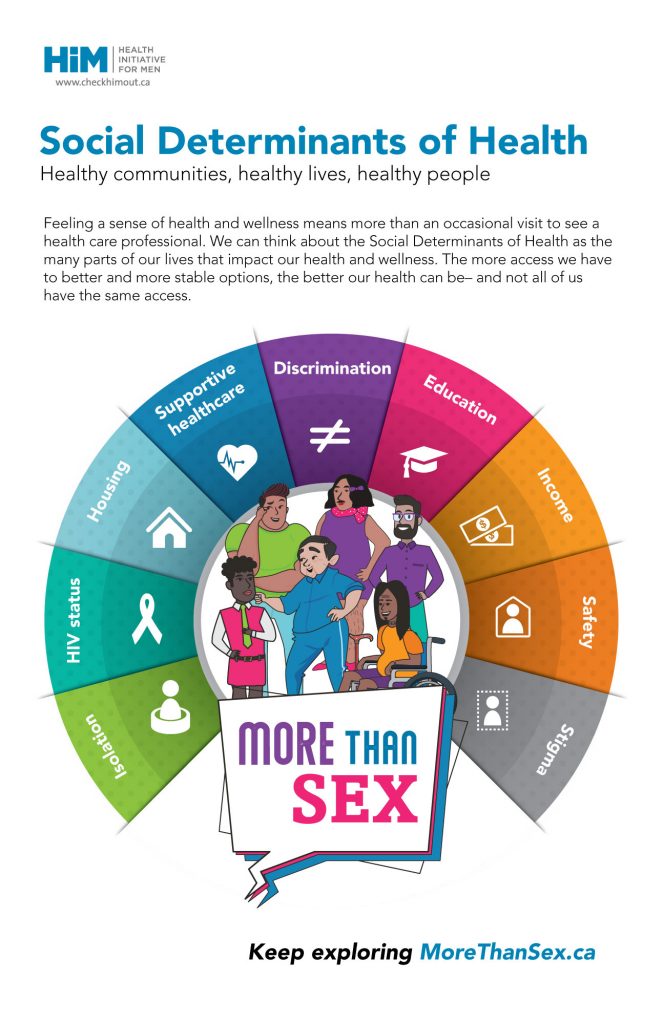

You may be surprised by the ways our social conditions can have an impact on our physical and mental health. This concept is captured in what we sometimes call Social Determinants of Health. Some examples include:

- A substantial and regular income makes a difference. People with higher income are able to afford food that is most nutritious, find a safe place to live, and pay for any out of pocket health expenses that we may have. Having a substantial and regular income means living with significantly less stress.

- Loneliness and Isolation often lead to experiencing more mental and physical illness, including stress. On the other hand, having a strong social network that supports us makes us feel more connected and more content.

- Racism (racial-based stigma, discrimination, and oppression) can make it difficult to access the things we need to thrive and sometimes just survive. This can include appropriate health care, housing, education, and work. Even if people of colour don’t always experience discrimination directly, knowing that we could experience race-based discrimination and other forms of violence at any point can harm our mental and physical wellbeing.

- Homophobia, Transphobia, heterosexism, and cissexism (sexual or gender-based stigma, discrimination, and oppression) remains a major barrier for a lot of us trying to meet our needs. These needs may be employment and housing, or support systems and the health care we need, to name a few. Sexuality based stigma, discrimination, and oppression can also lead to a number of mental and physical health including trauma and minority stress. Even when it’s not expressed as hate, living in a world that assumes our sexuality and gender experiences to be what they’re not can have real impact on our wellbeing.

- Ableism and lack of support for people with disabilities, can severely make a difference in the kinds of opportunities and resources available to us. This is true for disabilities that are immediately visible to others (like using a mobility scooter or wheelchair), and those that aren’t (like a mental health condition or invisible physical chronic illness). Lack of resources, stigma, and misunderstandings around disability can affect our health and well-being in many ways: fewer options for wheelchair accessible housing, and these options may be less affordable, needing time to take care of our depression or anxiety that we cannot get off from work, or health care providers making assumptions about our sexuality based on what they know of our medical history

We can try and better our wellbeing by trying to change our own social conditions. But almost always, these social conditions are a result of how our society is shaped and organized. To change the social conditions that affect our communities, we need to work together toward building stronger communities and demanding change from people in power.

Stigma & Lateral Violence

Stigma is a social power that excludes people who don’t fit in or are seen as “not normal”.

Queer and non-binary people often experience stigma even if we’re not out, we can be teased for seeming “different,” whether that be too feminine or masculine, too tall or too short, too thin or too large, having or not having body hair.

Stigma has been shown to have major effects on mental wellbeing. It can even cause a number of disorders including heightened anxiety, depression, and difficulty regulating our emotions.

But stigma also exists within our communities, which can be as harmful as the stigma we experience from the straight cisgender world. Stigma within our communities can happen:

Online when we’re rejected for not being white, masculine, muscular, or because we are living with HIV.

On dates when we’re criticized for our education level, how “out” we are, or what we do for work.

At community events when we’re told we’re not really men because we have a feminine sounding name and weren’t born with a penis.

At the bar when we’re judged that we can’t afford to buy a drink or don’t drink, speak with an accent, or are at the bar alone.

Stigma within queer communities is sometimes thought of as lateral violence. Lateral violence is when members of a marginalized group redirect their anger at other members of their own group. This can include hurtful gossip, shaming and blaming others, backstabbing or other acts that serve to socially isolate others.

Lateral violence occurs when people cannot combat the powerful who are responsible for their marginalization and so redirect their anger at their own community. “Lateral” violence is directed sideways. The aggressors are our peers or other people in similarly powerless positions.

While lateral violence is often talked about in the context of race, it is a useful lens to help us understand power dynamics in other marginalized populations. Another example of lateral violence seen too often in our communities are queer cis peers misgendering and mocking queer trans people in ways not so different from how straight peers may mock queer cis people.

Minority Stress

Queer people have been shown to experience a specific kind of stress because we are not part of dominant society. Our bodies have physical reactions to this stress, even if we do not notice it. Over time, this can result in health problems like anxiety and high blood pressure.

This stress can be caused by stigma and the possibility of experiencing stigma in a world that still marginalizes queer sexualities, gender non-conforming expressions, non-binary identities, Two-Spirit resiliencies, and trans experiences, histories, and identities.

Many of us experience fear and live with stigma and discrimination whether or not we’re “out”. Queer people who are less out still experience high levels of minority stress. Some of us experience minority stress accessing health care: having a health care professional assume our sexuality or misgender us based on what body parts we have.

This stress can also be caused by structural issues that more frequently effect queer people like poor social support and low socioeconomic status.

There are ways we can combat minority stress.

We can combat minority stress by de-stigmatizing our and our communities’ identities. We also need to work together to make sure that our communities have equitable access to the mental and physical health resources we need to thrive in a stigmatizing world.

It’s also important that we recognize minority stress in ourselves and take time for our minds. By taking care of ourselves we strengthen our ability to contribute to the well-being of our communities.

Trauma, Acute Stress, and PTSD

The word trauma is used for a number of circumstances, events and experiences that can impact our health and wellness. For example, an injury to a bone or muscle could be considered trauma.

When talking about mental health, trauma has a bit of a different meaning: here it means an injury of the mind, body, and spirit.

Trauma can happen at any time throughout our lives and can have an impact at many times throughout our lives.

Trauma is not always visible, but can feel very painful, stressful and confusing for those of us who live with it.

Sometimes trauma can lead us to behave and feel more agitated, nervous, careful, less trusting of others, more stressed, anxious, depressed and sometimes makes us want to use substances to help us get through the day.

For some of us, trauma can develop into something called PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder). PTSD is an acute reaction to trauma. PTSD is associated with panic attacks, extreme anxiety, hyper-vigilance, flashbacks and other troubling symptoms.Trauma can be caused by a number of things, and some of them are very unique and specific to our queer and gender diverse identities.

For example, we might be bullied, or excluded by peers and family early in life. We might experience violence, sexual assault, or rape. We might be involved in an accident, deal with being abandoned by people, or even have a particularly difficult break-up.

Trauma can also be passed down through our communities, nations and families. Indigenous Elders, leaders and researchers have told stories and published articles about how trauma can be passed down from generation to generation. Whether it is the impact of residential schools, HIV epidemic, the overdose crisis, colonization, violence and war, dislocation from home and community – trauma can have a major impact on our bodies, spirits, minds and communities.

Living with trauma can be challenging, but with the support of our communities, elders, culture and well-trained mental health professionals we can work to understand the things that happened to us (and our communities) and start to feel better in a way that makes sense to us.

Some of us might want to focus on managing [tooltips content=”Features of an infection or disease that we can feel or experience, such as pain while urinating.”]symptoms[/tooltips] associated with trauma through counselling and medication, while some of us might be more interested in therapy or ceremonies specifically designed to help us feel more connected to our communities and bodies again. What is most important is that we, our communities and culture get to make decisions about how we define trauma, how we engage with trauma, and how we help others with trauma. Trauma may be more or less a part of our lives at different times. Experiences of trauma do not stop us from being strong, healing, and thriving. Each of us has our own journey.

Building Stronger Communities: Resilience and Self-Advocacy

Queer men and non-binary people continue facing social stigma, discrimination, marginalization and oppression. However, it is also important to recognize historical and ongoing resilience and advocacy that are helping lead us to a world that is safer for everyone.

Our communities have a rich history of resilience and advocacy: from the fight for sexual and gender liberation and a real response to the HIV epidemic, to creating communities of care . This is true not only in places like Vancouver, but in communities around the world where queer and trans people face more intense oppression that is sometimes government-sponsored.

To make sure that our communities continue to blossom, it’s important that we keep building resilience and advocate for ourselves and our communities. It’s equally important that we do this keeping in mind the intersecting systems of power that affect members of our communities in different ways.

Practicing resilience and advocacy can take any number of forms.

For example:

- Holding politicians and decision makers accountable for addressing the health needs of our communities;

- Supporting Indigenous leadership, and demanding that Indigenous people and people of colour are respected and treated fairly in all contexts;

- Sponsoring queer refugees escaping more oppressive states.

Looking for where to start? Check out local community resources and find one that speaks to you and you want to get involved in!