HIV

Queer sex and experience mean so many different things that we could not possibly cover everything that in one resource. More Than Sex speaks to parts of what queer sex can mean, and some experiences that we may have when navigating queer sex, whatever our body or identity.

Many of us have been affected by HIV in one way or another: whether we live with HIV, accessed HIV prevention options, or HIV was one of the first things we learned about queer community. We may know friends or partners who are living with HIV, have lived through the early days of the HIV epidemic, or see the impacts of community advocacy about HIV today. We may have encountered HIV stigma when we have shared our gender or sexuality with others. Whether we’re living with HIV or not, we can all play a part in supporting each other as we navigate HIV.

HIV is a virus that is transmitted through specific types of sex, including anal sex and frontal/vaginal sex, that are popular within our communities. Because of this, HIV is categorized as a sexually transmitted infection (STI).

HIV has deeply impacted our communities since the 1980s. At the beginning of the HIV epidemic, very little was known about why people were getting sick, and it took time before the virus itself (what is now called HIV) was identified, and a test and treatment was developed. Inaction from government and health officials, as a result of homophobia, transphobia, and racism, delayed the development of treatment, testing, and health education. During this time, many activists fought to draw attention and resources to support people who were impacted. Many people in our community passed away in these years, as a result of stigma, and in the absence of medication.

Today, much more is known about HIV, including options for treatment, testing, and prevention. Medical advances mean that today, people living with HIV can live a long and healthy life. Despite the medical and educational breakthroughs that have been made since the 1980s, stigma remains, which is sometimes rooted in fear and discrimination towards sexual and gender minorities. In BC nowadays, these stigmas often have more of an impact on people living with HIV than the virus itself. Unfortunately, this stigma exists within our communities too.

What is HIV?

HIV stands for human immunodeficiency virus.

It is a virus that attacks the immune system, our body’s natural defense against diseases. HIV kills CD4 cells, which play a key part in our immune system. With fewer CD4 cells, it is harder for our body to respond to infections that we may be exposed to. Before killing our CD4 cells, HIV uses these cells to make more copies of itself.

Acute HIV

HIV is hottest at the start, meaning that HIV is most contagious in the first 8 to 12 weeks it is in a person’s body. This is often before we can even know HIV is in our body, since the most common tests can only detect HIV about three weeks or more after it is in our body. This first phase of HIV is called the acute phase.

Within a few days of transmission, the amount of HIV in our body soars. This is called the acute phase of an HIV infection. The high amount of HIV during the acute phase makes bodily fluids that have HIV much more infectious. Most HIV transmissions happen when a person with HIV is in the acute stage, often before they have had an HIV test.

It takes our immune system a few weeks to build up a response to HIV that lowers the amount of the virus in our bodies. HIV later decreases once the immune system can respond to suppress it. HIV transmission still happens after the acute stage, especially if a person is not taking treatment, but with the lower viral load it is not as likely.

Because the acute phase happens so soon after HIV transmission, a person in the acute phase usually won’t know that we have HIV at that time. Even if we do get a test during this time, the most advanced HIV test will not be able to detect the virus until it has been in our bodies for 10 to 12 days, or even 3 to 6 weeks, depending on which test we take, and it takes a few days to get results back from these types of tests. Some tests don’t detect the virus until three months after transmission, while most tests can detect HIV three weeks after transmission. Learn more about the different kinds of tests and where you can access them here.

Seroconversion Illness

When we first acquire HIV, we may experience seroconversion illness as the immune system responds to the virus.

Seroconversion is when a specific antibody develops and becomes detectable in the blood. With HIV, seroconversion takes a few weeks. Some HIV tests only look for these antibodies, meaning we may test negative during this period – even though we have HIV in our bodies.

Seroconversion illness is the name given to a set of symptoms caused by the body’s reaction to HIV. Seroconversion illness may occur about ten to fourteen days after acquiring HIV and last for one or two weeks.

Seroconversion symptoms include fever, sore throat, and rashes, as well as possibly nausea, vomiting, night sweats, joint or muscle pain, diarrhea, headaches, mouth ulcers, and swollen glands in the armpits, groin and neck.

70%-90% of people have a combination of these symptoms soon after HIV transmission, but few realize that these symptoms are HIV-related. Many people experience this as a flu. At the same time, many of these symptoms are also caused by other diseases or illnesses, and so having them does not mean we have HIV. Getting tested is the only way to know our status. [link to 1.8]

Asymptomatic Infection and AIDS

After the acute phase, a person may not have any symptoms of HIV for many years. This period is known as asymptomatic infection. Left untreated, the asymptomatic infection will weaken our immune system to the point we may develop other illnesses. Over years, without treatment, HIV without treatment can lead to AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome).

What is AIDS?

AIDS stands for acquired immune deficiency syndrome. This is not the same as HIV. AIDS may occur when a person’s immune system is severely weakened over years of living with HIV without treatment. Today, medication is available for people living with HIV that prevents AIDS.

AIDS is a syndrome that can only develop if we have an HIV diagnosis, and do not take medication for many years. Today, many people living with HIV never develop AIDS because of medication. AIDS cannot be transmitted between people, although if we have AIDS, we can transmit HIV.

In BC, AIDS is diagnosed when a person is living with HIV and has one or more infections that occur due to a low CD4 cell count. This group of infections is referred to as AIDS-defining conditions, and are uncommon among people who are HIV-negative. Some of these diseases include cervical cancer, recurrent pneumonia, and Kaposi’s sarcoma.

HIV Medications

Today, HIV medications can lower the amount of HIV in our body, in many cases, to an undetectable level. These medications can prevent and even reverse damage to the immune system, and prevents AIDS. With treatment, people living with HIV have a lifespan similar to people who are HIV-negative. Decisions about HIV medications are always ours to make.

In 2021, most HIV medication in Canada is in pill form, and people take one or more pills at the same time every day. In BC, these pills are provided at no cost to all residents. As of 2021, Health Canada has approved one HIV injectable treatment option, although in BC, injectable medications are only available if we pay for them ourselves.

If we are diagnosed with HIV, we are given more detailed information about what HIV medications may work best for us. We will get to make a decision about when to start HIV treatment, as well as what HIV treatments are best for us. Our health care providers will ask us to do [tooltips content=”Giving a blood sample for testing.”]bloodwork[/tooltips] to understand more about how much HIV we have in our bodies, and how our immune system is doing. HIV medications are prescribed by a medical doctor or nurse practitioner.

Starting treatment as soon as possible helps reduce the impact HIV has on our bodies over time, and can make it easier to reach an undetectable [tooltips content=”The amount of a virus in our bodies, most often measured in the blood. In More Than Sex, when we talk about viral load we mean the amount of HIV in the blood of someone living with HIV.”]viral load[/tooltips].

HIV medications are a class of medications called antiretrovirals (ARVs). HIV medication is also sometimes referred to as ART (antiretroviral therapy) or HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy). There are different types of antiretroviral medications, each of which focuses on a different step in the process for HIV to make copies of itself. By making it harder for HIV to make copies of itself, ARVs lower the amount of HIV in our bodies.

When a person’s [tooltips content=”The amount of a virus in our bodies, most often measured in the blood. In More Than Sex, when we talk about viral load we mean the amount of HIV in the blood of someone living with HIV.”]viral load[/tooltips] is [tooltips content=”When the someone living with HIV has a viral load 40 or less so isn’t detected by some HIV tests, and cannot be transmitted.”]undetectable[/tooltips], it also means that they cannot transmit HIV to others through sex: this is known as [tooltips content=”When someone living with HIV has a viral load so low that HIV cannot be transmitted to another person and that tests cannot detect the HIV.”]U=U[/tooltips], that undetectable equals untransmittable.

Viral Load

Viral load refers to the number of copies of HIV in a given part of the body or in a specific body fluid. In BC, viral load testing is part of regular HIV care offered to people living with HIV. These tests look to see how many copies of HIV are in a person’s blood.

Viral load is impacted by many factors about a person’s life and community, including HIV stigma, discrimination, whether or not a person has access to HIV medication, and what types of practical, cultural, community supports a person needs and has available. Over many years, a viral load will continue going up unless a person starts treatment using medicine referred to as antiretrovirals (ARVs).

Viral load is one of the most important factors as to whether or not a person will transmit HIV to another person. With HIV medication, viral load can become so low that people living with HIV cannot transmit the virus through sex.

Viral load is highest in the first 8 to 12 weeks when we acquire HIV, known as the acute phase. After the acute phase, a person’s viral load drastically drops because of how our immune system reacts. Viral load is also highest after years of living with HIV without taking medication, or if a person has an AIDS diagnosis. During these stages, it is easier to transmit HIV to another person. To find our more about the stages of an HIV infection, click here.

HIV medications (link to ARVs) also lower our viral load. When we first start medications, make changes to our medication, or miss doses of our medication, our viral load can increase.

The lower our viral load, the less likely HIV transmission is to take place.

In BC, people living with HIV who are receiving care are offered viral load tests as part of regular [tooltips content=”Giving a blood sample for testing.”]bloodwork[/tooltips]. Measuring viral load in the blood also gives us a good idea of viral load in our other body fluids, including body fluids that can transmit HIV: blood, cum ([tooltips content=”The fluid that contains sperm, and is created in the testes/external gonads.”]semen[/tooltips]), pre-cum, anal fluid, frontal/vaginal fluid, and human milk.

Undetectable Viral Load

When we take HIV medication properly, and we are able to take care of other aspects of our health, we may lower the amount of HIV in our bodies to levels that cannot be detected in lab tests. This is referred to as ‘undetectable’. Although HIV is undetectable in blood tests, it is still present in our bodies, although in very small amounts.

An undetectable viral load means that HIV is having a very small impact on our bodies, including our immune system. This lowered impact of HIV on our bodies can prevent many different HIV-related complications.

An undetectable viral load also means we cannot transmit HIV to our sexual partners. This is also referred to as U=U, that undetectable means untransmittable. Undetectable viral load is one strategy we can use to prevent transmitting HIV to our sexual partners. Whatever our viral load status, there are many options for us and our partners to prevent transmitting HIV.

The earlier we find out we are living with HIV and start treatment, the easier it will be to reach an undetectable viral load. If we are sexually active, or may come into contact with HIV through other activities such as sharing injection drug equipment, regular HIV testing is the best way to know our HIV status.

It can take time to get to an undetectable viral load. The amount of time it takes will vary based on our individual circumstances. Although most people can reach an undetectable viral load with time, there are some rare circumstances, such as if we have stopped and started HIV treatment many times, or if we are not taking HIV medication, an undetectable viral load may not be possible. Working with our health care providers is a great step towards having an undetectable viral load. Whatever our HIV status or viral load, and whatever our partner’s HIV status and viral load, we have many options to have hot sex without transmitting HIV.

HIV Transmission

To acquire HIV, the virus has to get into our bloodstream through a body fluid that has the virus. HIV is transmitted in the following six body fluids:

- blood

- cum (semen)

- pre-cum

- anal fluid (the mucus that lines the rectum)

- frontal/vaginal fluid

- human milk

Without these body fluids, HIV cannot be transmitted. Sweat, saliva, and urine alone do not transmit HIV. Contact with a person’s body (such as hugs, kisses, cuddling), and activities like sharing a meal or drink, cannot transmit HIV.

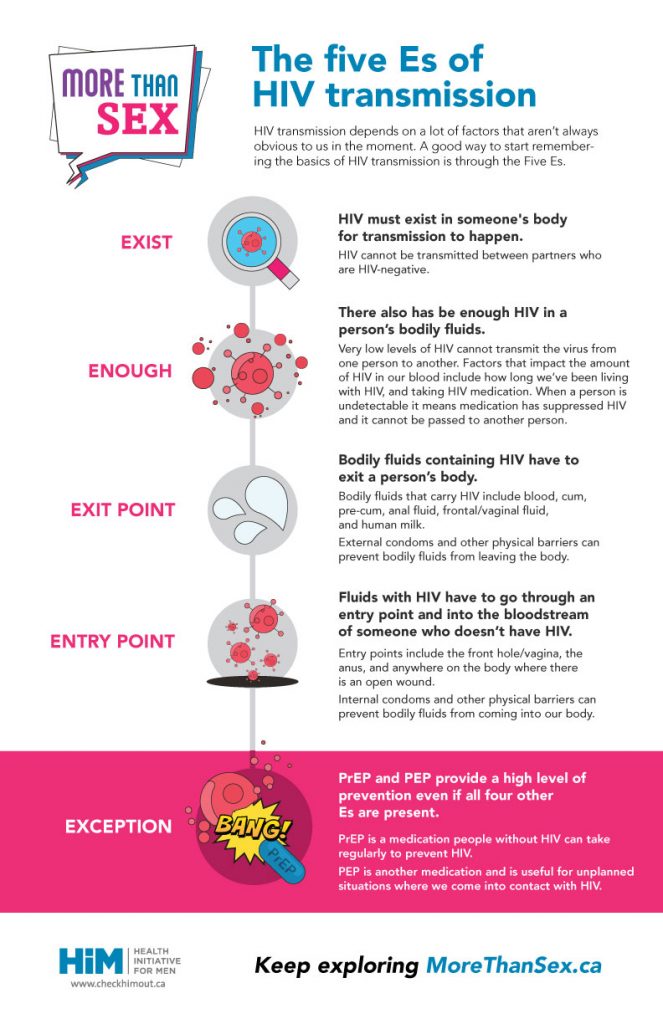

Five Es of Transmission

For HIV to be transmitted, all of the Four Es (exist, enough, exit point, entry point) must be present without the Fifth E (exception). HIV cannot be transmitted if only one, two, or three Es are present. If the fifth E (exception) is present, HIV cannot be transmitted even if all of the four Es are present.

In addition, just because all 4 Es are present – without the fifth E – does not mean HIV will be transmitted. Whether or not HIV is transmitted in these situations depends on many individual factors for each person, including whether or not we have an STI.

1st: EXIST

For transmission to happen, HIV must exist in someone’s body. HIV cannot be transmitted between partners who are HIV-negative. Getting tested is the only way to know our HIV status.

2nd: ENOUGH

For transmission to happen, there has to also be enough HIV in a person’s body fluids. Very low levels of HIV cannot transmit the virus from one person to another.

Viral load is the amount of HIV in a body fluid. Viral load is impacted by many factors, including how long a person has been living with HIV, and whether or not a person is taking HIV treatment. Higher viral loads are more likely to transmit HIV.

HIV medication can lower the amount of HIV in our body fluids to the point there is not enough HIV to transmit the virus to another person. This concept is also referred to as Undetectable equals Untransmittable (U=U). Our viral load is highest when we first contract HIV, often before we have been tested.

3rd: EXIT POINT

For transmission to happen, body fluids with HIV must leave the body of a person living with HIV through an exit point. Exit points include the urethra on a penis (for cum and pre-cum), and the nipple (for human milk). Body fluids may also exit a person’s body on another body part, a prosthetic, or a sex toy.

Body fluids that carry HIV include blood, cum, pre-cum, anal fluid, frontal/vaginal fluid, and human milk.

External condoms and other physical barriers can prevent bodily fluids that go through an exit point to make contact with another person.

4th: ENTRY POINT

For transmission to happen, fluids with HIV must go through an entry point into the body of an HIV-negative person. In other words, fluids with HIV must enter the body of someone who doesn’t have HIV.

HIV can enter our bodies through our mucous membranes. These include:

- the inner lining of the anus

- the inner lining of the front hole/vagina

- the foreskin and urethra (pee-hole) on a penis

Tears, fissures, or cuts in our mucous membranes can be an entry point. Anywhere the skin is broken or cut can also be an entry point.

Specific cells in the anus and front hole/vagina make them an easier entry point for HIV than the throat, mouth, and the foreskin and urethra on a penis.

Internal condoms and other physical barriers can prevent bodily fluids from going through an entry point.

There has to be both an exit point and entry point for transmission. For example, getting genital fluid on unbroken skin is an exit point without entry point, while making out presents entry points without exit points.

More information of specific kinds of sex and their transmission risks and pleasures can be found here.

5th: EXCEPTION- PrEP and PEP

PrEP is a strategy that prevents HIV in a partner who is taking it even if the 4 Es are present. PrEP is a medication taken by HIV-negative people that stops HIV transmission when it’s taken properly. This makes PrEP the exception to the other 4 Es.

PrEP stands for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, and specifically refers to HIV prevention.

PrEP is a medication a person without HIV can take to prevent HIV. PrEP is one strategy we can use to prevent acquiring HIV. Whether or not PrEP is right for us, there are many options for us and our partners to prevent transmitting HIV.

One other medication that can create an exception is PEP (Post Exposure Prophylaxis). This is an HIV medication those of us who are HIV-negative can take after the other 4 Es (exist, enough, exit point, entry point) have taken place to reduce our chances of becoming HIV-positive. PEP is useful for unplanned situations where we may acquire HIV. We need to start PEP as soon as possible, and no later than 72 hours after the other 4 Es have taken place. Taking PEP is not a recommended option on an ongoing basis.

Preventing HIV

There are many options to prevent HIV, whether we are living with HIV or we are HIV-negative. Throughout the HIV epidemic, people living with HIV have worked very hard to prevent transmitting HIV to others, often leading education and advocacy efforts that have strengthened our communities regardless of HIV status.

Preventing HIV is done by trying to stop one or more of the Five Es that can result in HIV transmission. For example, condoms create a barrier so that fluids containing HIV are blocked from reaching an entry point.

There are many prevention methods, and each of us has our own preferences around which prevention options work best for us. Some prevention options are more available than others.

Whether we choose medications like PrEP, or make decisions about what position to use (strategic positioning), there are many ways that we can prevent transmitting or acquiring HIV. We’ve gone into detail on each one and included details to keep in mind here.

Testing HIV

If we are HIV-negative, HIV testing is an important part of our health care, along with testing for other STIs. If we are living with HIV, we can still acquire or transmit other STIs which makes STI testing is an important part of our health care. STI testing may be part of our HIV care, or we may want to keep STI testing separate.

Since we can live with HIV for many years without any symptoms. HIV testing is the best way to know whether or not we have HIV. Knowing our HIV status has many health benefits for us as individuals. The earlier we get an HIV diagnosis, the earlier we can learn about our HIV care options, including medication, and supports and services that can support us.

We may want to get tested more often or less often depending on how often we may be coming into contact with HIV, and whether or not we are using prevention options.

In BC, there are a few different HIV testing options (more details further below). How often we many want test for HIV varies based on the kinds of sex we have, as well as what we know about our partners’ sex lives, STI status, and viral load.

How much HIV testing is right for me?

Knowing when to get tested for HIV can be tricky! The right number for us will depend on many factors, including how easy it is for us to get tested, and what information we have about our partners. If we are taking PrEP , HIV testing is especially important, and will be part of our PrEP care.

If we are having anal sex without using prevention options like condoms, PrEP, or undetectable viral load with partners whose HIV status and/or viral load we do not know, we recommend being tested every three months.

If we are having anal sex with one ore more prevention options, or if we are only participating in rimming (anal oral sex), or if we are having anal or frontal/vaginal sex only with only a few partners who we know to be undetectable or HIV-negative, we recommend being tested every twelve months. If we’re having lots of sexual partners, we can consider getting tested more frequently to make sure we’re on top of our sexual health regardless of the prevention strategies we’re using, or our partners’ HIV status.

If we experience an event where we know there is a possibility a body fluid with enough HIV entered our body, we recommend getting tested as soon as possible, based on the window period (learn about the window period for each test further below). These events might include having anal sex where a condom breaks, having sex with a person whose HIV status is unknown, having sex with a person who knows they are living with HIV and is not taking medications, or missing several PrEP doses around a time where we had anal sex.

For HIV-negative partners, we recommend that both partners get tested after six weeks to three months of consistent condom use without higher-likelihood events outside of the relationship. The six weeks to three months is to account for the window period of different HIV tests, so that both partners can be confident that they are HIV-negative. Talking with our health care provider around testing window periods can help us determine the relevant window period for our situation.

We can also use testing as part of decision making about whether or not to use other prevention options. For example, if we know a specific partner is also HIV-negative, we can choose to stop using condoms or stop taking PrEP without a possibility of HIV being transmitted. We also know there is no possibility of transmitting HIV when we have anal sex without condoms or PrEP if our sexual partner is living with HIV and has an undetectable viral load and does not have an STI.

Types of HIV Tests:

BC has a few different options for HIV tests, although they are not all available in every place. We do not need to know what type of HIV test(s) we want before getting tested. Our health care provider will be able to explain the available options. A HIM Health Centre, a sexual health clinic, our family doctor, or a walk-in clinic can all provide options for us to get an HIV test. Find a testing site near you here.

Currently available HIV tests are accurate only after HIV has been in our bodies for 10 to 12 days or three weeks, depending on the type of test. There is no HIV test that can tell us if we have HIV in the first week after coming into contact with the virus. The amount of time between when an infection (in this case, HIV) enters our body, and when the test will find it, is called the window period. Learn more about the window periods of different HIV tests below.

It takes time between when HIV settles in our body and when HIV tests can find it. The window period is the length of time required between when someone acquires HIV and when it can be detected by an HIV test.

Tests have different window periods because they look for for different things in our bodies:

- HIV: the virus itself

- immune system to activate, especially by making antibodies.”]Antigens[/tooltips]: a specific part of the virus; detectable before antibodies

- Antibodies: produced by our immune system in response to HIV; detectable after antigens

In BC, the standard HIV test is called the 4th generation Enzyme Immunoassay Test (EIA) test, which looks for both antigens and antibodies. In most cases, this is the test we will receive when asking for an HIV test in BC. It can take up to one week to get results back from the laboratory where our blood is tested.

- Tests and detects: Antigens and antibodies the immune system produces in response to HIV.

- Window period: 3 weeks after contraction for 90% of people; up to three months for others

- Method: Blood drawn from arm and lab analysis.

- Analysis time: 5-7 days lab analysis.

We may have experience receiving Early (NAAT/RNA) tests, which looks for HIV itself. This test used to be available in situations of direct contact with HIV and/or there are symptoms of acute HIV but is no longer readily available in BC. This test can find HIV as soon as 10-12 days after it enters our body.

- Window period: 10-12 days after contraction.

- Method: Blood drawn from arm and lab analysis.

- Analysis time: 5-7 days lab analysis.

Some clinics also have a rapid test (point of care or P.O.C.) test available. This test provides results in just a few minutes. This test only looks for antibodies.

- Tests and detects: Antibodies the body produces in response to HIV.

- Window period: 3-4 weeks after contraction for 90% of people; up to three months for others.

- Method: Blood from a finger poke

- Analysis time: A couple of minutes

Accessing Results of an HIV Test

Whether we get tested at a sexual health clinic, HIM Health Centre, walk-in clinic, emergency department, or primary care providers office, we have a right to know the results of our HIV test.

We can also get tested for HIV online if we have no symptoms, at Get Checked Online, which is available at participating labs around the province. Testing online requires an internet connection, and access to one of the participating labs.

If our results are nonreactive, this typically means they are negative and that the test did not pick up the STI they were testing for in our body. Often this means that we will not receive a phone call from the location where we got tested. Sometimes, we are given a number we can call in case we don’t hear anything and want to confirm our negative results.

If our results are reactive, the sample will be sent for further testing to confirm, or we may be called back to the clinic to give a second sample. If the results are then confirmed with a second test to be reactive, this means that our bodies have developed immune system in response to viruses.”]antibodies[/tooltips] to HIV, and this means that the result is likely positive.

Did you get tested at a HIM Health Centre? You can access your results with these contact numbers.

There is much support available for people recently diagnosed with HIV. A healthcare provider, usually a nurse, will call us to follow up and see how we are doing. If we have a new positive diagnosis and are in BC, a public health nurse will call us and follow up, and offer to support us. This nurse will also offer to work with us to let our recent sexual partners know they may want to get tested.

Living with HIV

Many people in queer communities live with HIV. With HIV medication a person with HIV can live a full, long, healthy life that includes a satisfying sex life.

Currently, HIV has no cure. However, there are a number of medications that limit how HIV impacts our health, allow people living with HIV to have similar life spans to people who are HIV-negative, and prevent HIV from being transmitted through sex, pregnancy, or childbirth.

Treatment options have improved a lot since HIV first appeared. In many cases, this treatment means taking a pill once-a-day with limited side-effects.

There are many different medications we can take to manage HIV. Together, these are known as antiretroviral (ARV) therapy. We can discuss which treatment options are right for our situation with our health care provider.

In BC, people living with HIV have access to treatment for free through the Drug Treatment Program. For those of us who don’t have medical insurance coverage in Canada, we can discuss options for accessing treatment with the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS.

There are many health benefits to starting HIV treatment as soon as possible from when we become HIV-positive. This is one reason why regular HIV testing may be something we choose to include in our sexual health routines.

Recent studies have connected early start to treatment with better health outcomes for people living with HIV, including reaching undetectable viral load. It is always up to us as individuals how we manage living with HIV. Connecting with a trusted health care provider allows us to make informed decisions about our health.

- HIV treatment works best when we are able to take medication consistently every day, at the same time. Missing a dose here and there will not impact our health.

- Many people, including other people living with HIV, are available to help us take medications consistently through our local HIV/AIDS service organizations.

- If we know that we cannot take medications consistently each day at this point in our lives, we may want to consider starting treatment when that changes.

- If we miss doses regularly, our medication can stop working. HIV is a very smart virus that can change quickly and become resistant to medication if we miss doses regularly. If we become resistant to a specific HIV medication, we will not be able to use that medication again. We will still have other options for HIV medications.

- If we know there is a time where we cannot take medications in advance, we can work with our care providers to make a plan to take a break from treatment.

- If we realize that taking medication every day is not working for us right now, we may want to talk to a care provider about stopping treatment for now, and trying again at another time.

Disclosing HIV status

People living with HIV have the right to decide if and when to disclose our HIV status. There are very few situations where the law in Canada requires HIV disclosure. We do not have to disclose our HIV status to our employers, or our friends, gyms, or social spaces. There are policies and laws in place in BC that may require us to disclose our HIV status in certain scenarios where paramedics or firefighters provide health care, and in certain sexual scenarios. Unfortunately, these rules are based on HIV stigma and inaccurate information.

It is our responsibility to decide whether or not we want to talk to our sexual partners about HIV status, whether ours or theirs. However, it is important to know the courts in Canada have created a legal duty to disclose that we are living with HIV before:

- sex without a condom, and/or

- sex when our viral load is 1,500 copies/ml of blood or higher

This reflects incorrect information about how HIV is transmitted during sex, as we know sex without a condom when a person’s viral load is undetectable cannot transmit HIV, and condoms prevent HIV from being transmitted.

Each province has its own guidelines about how to respond in situations of HIV non-disclosure. In BC, the guidelines say people living with HIV will not be prosecuted if we have only oral sex and no other HIV risk factors are present. They also say if we have sex without a condom and are taking HIV medication and our viral load is under 200 copies/ml for at least four months, we will not be prosecuted. However, BC continues to use outdated science to make decisions about HIV prosecutions, which is harmful to our communities.

This legal duty is unjust and does not prevent HIV from being transmitted in our communities. This legal duty furthers HIV stigma and misinformation that harms our communities. It also ignores the reality that throughout the HIV epidemic, people living with HIV have often led work in our communities to prevent transmitting HIV.

Whatever our HIV status, we can take responsibility for our own sexual health. HIV stigma – including in sexual spaces online and in-person – is a barrier for all of us to have open conversations about HIV and sexual health. In some cases, HIV-negative people reject sexual partners because of their HIV status, despite many options to have sex without transmitting HIV. This rejection makes it harder for all of us to talk about HIV and sexual health openly

People living with HIV have been charged under the criminal law for not disclosing HIV status to sexual partners, and across Canada, the federal and provincial governments have taken different approaches to such prosecutions.

There is a lot of work being done by organizations like HIM to inform decision-makers on the harms of harsh [tooltips content=”Not sharing information”]non-disclosure[/tooltips] laws. Until these legal system makes a commitment to stop charging people living with HIV for situations where there was no intent to transmit HIV, HIM will continue to provide information about the legal realities of having sex as people living with HIV.

A detailed guide to [tooltips content=”Sharing information. In More Than Sex, we talk about disclosure in the context of HIV status, gender,”]disclosure[/tooltips] and its legal implications written especially for cis gay men can be found here.

HIV and other STIs

Untreated sexually transmitted infections (STIs) make it easier to transmit or acquire HIV, whether we live with HIV or are HIV-negative.

Having an untreated STI can make us more vulnerable to acquiring HIV. That’s because inflammation caused by STIs can make it easier for HIV to infect and replicate through blood cells.

If we’re living with HIV, the response of the immune system to having an STI can increase our viral load. This can have negative effects to our wellbeing, and also makes it easier to transmit HIV to sexual partners.

Want to know more? Get a full rundown of how each STI interacts with HIV in STIs 101!

Regular testing can help us detect and more quickly treat STIs, and is a strategic way of lessening our vulnerability to HIV regardless of our status.

What Are STIs?

STI stands for sexually transmitted infection. STIs are caused by bacteria, viruses, or parasites that are transmitted and acquired during different types of sexual contact and activities. STIs can be a part of having sex, yet, many of us experience stigma if we have an STI. A lot of stigma comes from misinformation. This resource aims to provide accurate, stigma-free information to our communities.

Most often, STIs do not have any symptoms. Most STIs are curable and all are treatable!

The only way to know for sure whether or not we have an STI is to get tested. Depending on where we live, there are many different options for testing. Getting tested is the first step to finding treatment options that are right for us.

Getting positive test results can be disappointing, and can bring up all sorts of feelings about ourselves and our relationships. Depending on the STI, we might be learning to live with an STI for the rest of our lives, or need to make a short-term change for medication to cure us. HIM is here to help navigate these feelings.

If we acquire an STI, a nurse will work with us in letting our recent partners know they’ve come into contact with an STI. We can tell our partners anonymously through email or SMS, by getting in touch with them one-on-one, or by passing on information to public health to let our partners know anonymously. As much as open and honest communication is an important part of sex, so it is in sexual health!

Below is information on specific STIs that are common in our communities. This information includes how each STI is transmitted, what symptoms we might feel if we have them, how we test for and treat them, and how they interact with HIV. There’s also information about infections that can be related to sex, but aren’t STIs, like bacterial vaginosis.

Bacterial Vaginosis (BV)

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) happens when the healthy bacteria inside our front hole/vagina becomes unbalanced. There are a variety of factors that can cause BV, including – but not only – sexual contact. Only people with a front hole/vagina can get BV, which is a very common (and treatable!) infection.

If left untreated, BV can cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and lead to fertility issues for some of us who have Fallopian tubes and a uterus. Routine screening for BV can help prevent complications like PID.

How is BV caused?

Our front hole/vaginas have many types of bacteria inside them. The makeup of these bacteria is different from person to person. While there is a lot that is unknown about these bacteria, we know they play an important role in our overall health. BV happens when the make up of bacteria inside our front hole/vagina becomes unbalanced. BV is more common in our teen years through until our mid-forties.

It is not entirely clear what causes the balance of bacteria in our front holes/vaginas to shift. One factor that is known to shift the balance of bacteria in our front hole/vagina is douching. Using water or douching products inside our front hole/vagina disrupts the bacteria and is associated with BV. Using soaps of any kind, but especially strong or scented soaps, to clean our front hole/vagina is also associated with BV.

Factors that are linked to higher rates of BV include:

- smoking cigarettes

- taking testosterone

- having an IUD

- having higher numbers of sexual partners

- having a new sexual partner

- having another STI

Sometimes, our bodies and our partners’ bodies have different bacteria on our skin. These differences in our naturally occurring bacteria can cause BV when they enter our front hole/vagina. This can be bacteria from any body part: hands used in fingering or fisting, penises, prosthetics, or shared sex toys. BV may also be passed between people who both have a front hole/vagina when fluids from one front hole/vagina is transferred to another person’s. When we have sex with the same person multiple times, our bodies get used to this new bacteria, and we may not develop BV as often.

How do we test for BV?

Testing for BV is usually done with a swab of the front hole/vagina, and an exam. The swab can be done by ourselves as a self-swab, or by a healthcare provider during the exam. Swabs are available from a healthcare provider after a conversation about our symptoms.

Test results are accurate from the time we have symptoms of BV. In BC, it takes about ten days to get test results. If we test positive, we may want to tell any of our sexual partners who have a front hole/vagina so they can get tested too, since BV is not transmitted to people with penises.

What are the treatment options for BV?

Antibiotics are used to treat BV. When taking antibiotics, it is especially important to follow the instructions from our health care providers. Even though our symptoms often go away within a few days, it is important to continue our antibiotics as prescribed even after symptoms disappear. Missing doses, or stopping our antibiotics too soon, can prevent them from working and can lead to BV returning.

Antibiotics to treat BV are available for free in British Columbia in public health settings, such as at HIM Health Centres or other sexual health clinics. If we are getting tested or treated by a family doctor, walk-in clinic, or other primary care setting, they may not have these medications on hand. We can ask about our options to access publicly funded treatment options (sometimes these clinics can order them directly), or they may give us a prescription to fill and pay for at a pharmacy.

If we are taking testosterone and have BV multiple times per year, our health care provider may suggest treatment that involves placing an estrogen cream or tablet in our front hole/vagina.

Without treatment, BV can cause complications in pregnancy, can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, and can increase our risk of getting or transmitting STIs and HIV.

How do we prevent BV?

One way we can prevent BV is by not douching. Our front holes/vaginas are able to clean themselves, and do not need douches, washes, or soaps to stay clean.

Using barriers on body parts, shared toys, or prosthetics, that we are inserting into our front hole/vagina, helps to prevent BV.

Whether or not we use barriers, like condoms and gloves, washing our hands before sex, and encouraging our partners to do too, can help prevent BV.

If we are having both anal sex and frontal/vaginal sex, changing condoms or cleaning the body part before changing from anal to frontal/vaginal sex will help before bacterial infections, including BV. Another option is going from frontal/vaginal sex to anal sex only, not the other way around.

We cannot transmit BV to sexual partners who do not have a front hole/vagina.

What are the symptoms of BV?

Many of us will not have symptoms of BV. If we do have symptoms, they may include:

- Discharge from the front hole/vagina that is thin, gray, white or green.

- Itching or irritation in our front hole/vagina.

- Burning during urination.

- Foul-smelling fish-like odour.*

*All genitals have unique, distinct smells that are healthy, common, and part of having sex. Most genital infections do not have a smell. In the case of BV, a foul-smelling odor that may smell like fish, may develop.

BV and HIV

Changes to the bacteria in our front hole/vagina can make HIV transmission easier.

For people living with HIV: The response of the immune system to having an infection can increase our viral load. Increased viral load makes it easier to transmit HIV to sexual partners.

For people who do not have HIV: inflammation caused by infections can make it easier for HIV to enter the bloodstream.

Chlamydia

Chlamydia is a very common STI caused by bacteria. The bacteria often infects the urethra as well as the anus, throat, and front hole/vagina. In rare cases, it can affect the eyes.

If left untreated, chlamydia can cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and lead to fertility issues for some of us who have Fallopian tubes and a uterus. Routine screening for STIs, including chlamydia, can help prevent complications, including PID.

How is Chlamydia Transmitted?

Chlamydia is transmitted very easily through condomless anal frontal/vaginal sex or oral sex, touching or rubbing genitals together with a partner, or sharing a sex toy that hasn’t been sterilized or wasn’t covered with a condom. In very rare cases, chlamydia can be transmitted if we get semen or frontal/vaginal fluid into the eye.

We can transmit chlamydia whether or not we have symptoms.

How Do We Test for Chlamydia?

Chlamydia testing is part of routine STI testing. Getting tested for chlamydia is simple and painless. Testing uses a urine sample and, if we have anal, oral, or frontal/vaginal sex, a swab.

We provide a urine sample by peeing into a cup. Anal, throat, or frontal/vaginal swabs may be collected by our health care providers, or in some cases, we may be able to collect our own swab (called self-swab). We can ask to self-swab if we are seeing a healthcare provider and would be more comfortable with swabbing ourselves. Urine samples and swabs are tested in a lab to check if it is chlamydia. Results should be available within a week or two, depending on which region we live in. HIM offers testing for Chlamydia at our Sexual Health Centres.

The test cannot detect chlamydia until it has been in our body for 2-6 weeks. Testing detects chlamydia even if we do not have symptoms.

Chlamydia is an STI that is reportable. If we test positive, public health will work with us to notify our current and recent partners. We can choose to let our partners know ourselves that they may have come in contact with chlamydia and may want to get tested. The goal of this process is to let our sexual partners know they may have been in contact with chlamydia so that they can make informed decisions about the sex they’re having and receive treatment. Through this process, our partners will be able to access chlamydia treatment without waiting for a test result.

What Are the Treatment Options for Chlamydia?

Chlamydia is easily treated by antibiotics. It is very important to closely follow the instructions and take all the prescribed pills. If we skip some pills, or don’t take them as instructed, they may not be effective in getting rid of the infection and we may not be cured. When we start taking the pills, it is important to avoid having sex for 7 days, beginning on the day we start taking the antibiotics as we can still transmit chlamydia during that 7 day period through contact with cum (semen), pre-cum, anal fluids, or frontal/vaginal fluids. We can still explore our sexuality through masturbation, or have virtual sex via phone or messaging during this time.

Having chlamydia once will not make us immune to getting it again. If we come into contact with the bacteria we might pick it up again and we would need to be treated by antibiotics again.

Antibiotics to treat chlamydia are available for free in British Columbia in public health settings, such as at HIM Health Centres or other sexual health clinics. If we are getting tested or treated by a family doctor, walk-in clinic, or other primary care setting, they may not have these medications on hand. We can ask about our options to access publicly funded treatment options (sometimes these clinics can order them directly), or they may give us a prescription to fill and pay for at a pharmacy.

How Do We Prevent Transmission?

Chlamydia is transmitted through body fluids. Regular use of condoms, both internal and external, will reduce the chance of transmitting chlamydia and other STIs. Having fewer sexual partners will also reduce the chance of acquiring chlamydia.

We can prevent transmission by following instructions provided with our treatment, and holding off on having sex with a partner who is experiencing chlamydia symptoms, is being treated for chlamydia, or has just finished chlamydia treatment.

Getting tested for chlamydia regularly allows us to get treatment quickly which helps prevent us from transmitting chlamydia to other partners.

HIV-specific prevention strategies, including PrEP, do not reduce the chance of transmitting or acquiring chlamydia.

What Are the Symptoms of Chlamydia?

Since most of us will not have noticeable symptoms, the only way to know if we have chlamydia is to get a test. About half of us with an ejaculating penis and most of us with a front hole/vagina will have no symptoms at all. If there are symptoms they usually appear within one to three weeks after transmission.

Those of us with an ejaculating penis may experience symptoms such as a cloudy or watery discharge, pain when urinating, burning or itching in the urethra, and pain and swelling of the testicles. For those of us with a front hole/vagina, the symptoms we may experience include a change in our front hole/vagina or vaginal discharge, pain when urinating, pain in the belly or lower back, pain during frontal/vaginal sex, and bleeding between periods or after frontal/vaginal sex.

Chlamydia in the anus will probably have no symptoms, though discomfort and some discharge are possible.

Chlamydia in the throat is usually without symptoms. In the eye, chlamydia can cause pain, redness, and discharge (conjunctivitis).

Rarely, chlamydia can occur in other mucous membranes if fluids from sex come into contact with them. For example, if we have semen in the eye, we may have yellow discharge from the eye.

Chlamydia and HIV

Having an untreated STI like chlamydia can make HIV transmission easier.

For people living with HIV: The response of the [tooltips content=”A network of cells, tissues, and organs in our bodies that fight infections and diseases.”]immune system[/tooltips] to having an STI can increase our [tooltips content=”The amount of a virus in our bodies, most often measured in the blood. In More Than Sex, when we talk about viral load we mean the amount of HIV in the blood of someone living with HIV.”]viral load[/tooltips] Increased viral load makes it easier to transmit HIV to sexual partners.

For people who do not have HIV: inflammation caused by STIs can make it easier for HIV to enter the [tooltips content=”Part of the body’s circulatory system that transports blood throughout the body.”]bloodstream[/tooltips].

Genital Herpes

Herpes is a viral infection caused by two strains of the herpes simplex virus (HSV): HSV-1 and HSV-2. This virus is most noticeable when we experience an outbreak of sores on our skin or in our mucous membranes. These sores often start as blisters, which then open and form ulcers.

HSV-1 is usually associated with cold sores on or around the mouth, while HSV-2 causes herpes around the genitals, anus, and legs. We can still transmit HSV-1 from the mouth to the genitals or HSV-2 from the genitals to the mouth.

How Is Genital Herpes Transmitted?

Herpes can be transmitted by any contact with skin where the virus is present. Skin-to-skin contact can happen during anal sex, frontal/vaginal sex, oral sex whether giving or receiving, kissing, as well as sharing a sex toy (cock, plug, etc.).

Herpes is also transmissible from parent to child during birth. Herpes is most transmissible when a person has an outbreak or flare-up, causing painful sores or blisters to be present, but the virus is also transmissible even when there are no visible symptoms to a lesser extent.

There are options we can use to do these activities in ways that minimize the chances of transmitting herpes.

How Do We Test for Genital Herpes?

The only conclusive test for genital herpes is a swab and examination of sores and/or blisters by a health care provider. This test is most accurate when done within 72 hours of sores or blisters appearing.

Unfortunately, blood tests cannot conclusively diagnose genital or oral herpes. Since these tests are inconclusive, blood testing is only recommended in specific circumstances, such as if we are pregnant and have a sexual partner with a herpes diagnosis, if we have a sexual partner with a herpes diagnosis, and for people living with HIV and their sexual partners.

There are two types of blood tests. The non-type specific blood test will say whether or not we have antibodies to the herpes virus. It cannot tell us if we have oral or genital herpes. The type-specific blood test will say whether we have antibodies for HSV-1 or HSV-2, but not where on our bodies we have herpes. This test is usually only available to people if we pay for it (about $130), even if we have MSP.

Since herpes testing is limited, and herpes is quite common, herpes is not part of routine STI testing. If we are concerned about herpes specifically, or we have symptoms, we can let our health care provider know.

If we test positive for herpes, we may want to consider letting any past or current sexual partners who may be impacted know. Since herpes testing is not part of routine STI tests, letting our partners know means they will be able to ask for testing as needed. If we choose to do this, we can do so ourselves, or use tools like Tell Your Partners anonymously through email or SMS.

What Are the Treatment Options for Genital Herpes?

There is currently no cure for herpes infections. However, there are treatment options to make outbreaks easier to manage, and in some cases, prevent outbreaks. Whether or not treatment is right for us will depend a lot on our own experiences and what symptoms we have.

During outbreaks, antiviral medication can relieve pain and itching and help the sores to heal faster. The treatment works best if it is started soon after an outbreak begins, so we may want to ask our health care provider for a prescription to have on hand. That way, we can start medications as soon as we feel warning signs of an outbreak without having to get an appointment and pick up medications. Antiviral medications can stop an outbreak, make an outbreak shorter, or make it less painful.

If we experience six or more outbreaks per year, it can be helpful to take a low dose of antiviral medication on a regular basis. Talking to a health care provider about our options can give us more information.

Whether or not we are taking antiviral medication, there are other options to help with herpes symptoms. We can take Tylenol or Advil to reduce any pain that we may experience with an outbreak, or using an ice pack – wrapped with a soft fabric – against sore skin. During outbreaks, we may want to choose loose fitting clothes and cotton underwear to prevent additional irritation of or skin.

How Do We Prevent Transmission?

Unfortunately, there is no one totally effective prevention option for herpes because this virus can be transmitted through contact with skin, whether or not symptoms are present. Barriers such as condoms and dental dams reduce the transmission of herpes, but only cover part of the genital area where the herpes virus may be present.

We can reduce the chances of transmission if we reduce sexual contact during an outbreak for ourselves or our partners. This may mean finding ways to have sex that avoid contact with the specific part of the body where there are blisters or sores.

We can also reduce our chances of transmitting or acquiring herpes by limiting our number of sex partners.

Antiviral medications lower our chances of transmitting herpes.

HIV-specific prevention strategies, including PrEP, do not reduce the chance of transmitting or acquiring herpes.

What Are the Symptoms of Genital Herpes?

Symptoms vary from person to person. Many people who have herpes never have symptoms, or the symptoms are so mild that we don’t realize they have the virus. Many people will not have symptoms when we first get herpes. It may be months or years before any symptoms appear.

We may experience herpes outbreaks. During an outbreak, the virus causes painful blisters or sores in or around the penis, front hole/vagina, anus, mouth (known as cold sores), throat, and sometimes on the thighs, buttocks, or other areas. These will often eventually rupture and turn into open, shallow sores that take anywhere from a few days to a few weeks to heal. Over time, outbreaks heal faster and become less painful and less frequent as time goes on.

Before blisters appear, the skin around where they will appear may itch, tingle or feel numb. Outbreaks may also cause us to feel tired, with flu-like aches and swollen glands, and cause discharge from the penis, front hole/vagina, or anus.

After the first outbreak of blisters, the virus moves into the nerve cells and becomes inactive. It springs to life every once in a while, and then travels down the same nerve causing another outbreak. Being stressed, run-down, sick or sunburned can trigger an outbreak. Having an impaired immune system can also cause genital herpes to be more severe.

The number of outbreaks usually slows down after a few years. Some people will have outbreaks more often than others. Many people who have genital herpes never get blisters or sores again after the first outbreak.

Herpes and HIV

Genital herpes is one of the most common infections among people living with HIV.

Depending on the sex we are having, we may want to ask about routine herpes testing. If we are living with HIV, herpes outbreaks can last longer and be more severe. Herpes may also impact our HIV health.

Treatment for herpes may require higher doses if we are living with HIV. In this case, letting our health care provider know our HIV status will help us get the treatment that will work best for our overall health.

Having an untreated STI like herpes can make HIV transmission easier:

For people living with HIV: When our [tooltips content=”A network of cells, tissues, and organs in our bodies that fight infections and diseases.”]immune system[/tooltips] responds to an STI, it can increase our HIV [tooltips content=”The amount of a virus in our bodies, most often measured in the blood. In More Than Sex, when we talk about viral load we mean the amount of HIV in the blood of someone living with HIV.”]viral load[/tooltips] and make it easier to transmit HIV to our sexual partners

For people who do not have HIV: inflammation and sores caused by STIs can make it easier for HIV to enter our [tooltips content=”Part of the body’s circulatory system that transports blood throughout the body.”]bloodstream[/tooltips].

Gonorrhea

Gonorrhea is a very common STI caused by bacteria.

The bacteria often infects the urethra, which is the tube in the genitals that urine, and for some, semen exits the body. Gonorrhea can also infect the throat, anus, and front hole/vagina. In rare cases, gonorrhea can infect the eyes and intestines.

If left untreated, gonorrhea can cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and lead to fertility issues for some of us who have Fallopian tubes and a uterus. Routine screening for STIs, including gonorrhea, can help prevent complications like PID.

How Is Gonorrhea Transmitted?

Gonorrhea is transmitted very easily. If we or a partner have gonorrhea it can be transmitted through condomless anal sex, front hole/vagina sex, or oral sex, touching or rubbing genitals together with another person, sharing a sex toy that has not been sterilized or wasn’t covered with a condom, or getting semen or frontal/vaginal fluid into the eye. Gonorrhea can be transmitted even if we do not notice symptoms.

How Do We test for Gonorrhea?

Gonorrhea testing is part of routine STI testing. Getting tested for gonorrhea is simple and painless. In most cases, a urine sample is collected or the area of the body is swabbed. Urine samples and swabs are tested in a lab to check if it is chlamydia. The window period for a gonorrhea test is 7 days and results should be available within a week. HIM offers testing for gonorrhea at our Sexual Health Centres.

Gonorrhea is an STI that is reportable. If we test positive, public health will work with us to notify our current and recent partners. We can choose to let our partners know ourselves that they may have come in contact with gonorrhea and may want to get tested. The goal of this process is to let our sexual partners know they may have been in contact with gonorrhea so that they can make informed decisions about the sex they’re having and receive treatment. Through this process, our partners will be able to access gonorrhea treatment without waiting for a test result.

What Are the Treatment Options for Gonorrhea?

Gonorrhea is a bacterial infection that is treated with antibiotics, usually ceftriaxone as an injection in the muscle or for some people a short course of pills.

People who test positive for Gonorrhea infection, or are notified that they have been in sexual contact with someone with gonorrhea, or have visible discharge during the nurse assessment will receive the antibiotic treatment. Previously, gonorrhea was treated using oral medications only, but ongoing surveillance has shown that treatment via Ceftriaxone injection to be more effective and is accepted as best practice in many provinces including BC.

If we get gonorrhea treatment, it can take up to one week to cure the infection. During this time, it is important that we do not have sex that can transmit gonorrhea. Sometimes after receiving these antibiotics, we will be offered follow up testing to make sure that the antibiotic treatment was successful.

Having gonorrhea once will not make us immune to getting it again – if we encounter the bacteria, we might pick it up again, and we would need to be treated by antibiotics again.

Antibiotics to treat gonorrhea are available for free in British Columbia in public health settings, such as at HIM Health Centres or other sexual health clinics. If we are getting tested or treated by a family doctor, walk-in clinic, or other primary care setting, they may not have these medications on hand. We can ask about our options to access publicly funded treatment options (sometimes these clinics can order them directly), or they may give us a prescription to fill and pay for at a pharmacy.

How Do We Prevent Transmission?

Regular use of barriers, especially external or internal condoms, will reduce the chance that gonorrhea and other STIs may be transmitted. Having fewer sexual partners will also reduce the chance of acquiring gonorrhea.

Routine sexual health check-ups include a test for gonorrhea.

Getting tested for gonorrhea regularly allows us to get treatment quickly which helps prevent us from transmitting gonorrhea to other partners.

HIV-specific prevention strategies, including PrEP, do not reduce the chance of acquiring or transmitting gonorrhea.

How Are the Symptoms of Gonorrhea?

Many people do not notice symptoms of gonorrhea. The only way to know whether or not we have gonorrhea is to get tested.

If we do notice symptoms, they usually appear two to seven days after infection.

We may experience a burning sensation, and there may be green, white, and/or yellow discharge coming from the penis or front hole/vagina. If we have testicles, we may experience a painful swelling called epididymitis. If we have a front hole/vagina we may experience pain in the lower abdomen, heavier periods and possibly bleeding between them, and in rare cases bleeding after frontal/vaginal sex.

If we have gonorrhea in the rectum, there may be a discharge from the anus and pain or discomfort. Gonorrhoea in the throat usually causes no symptoms. Gonorrhea in the eye will often cause inflammation (redness) called conjunctivitis.

Gonorrhea and HIV

Having an untreated STI, including gonorrhea, can make HIV transmission easier:

For people living with HIV: The response of the [tooltips content=”A network of cells, tissues, and organs in our bodies that fight infections and diseases.”]immune system[/tooltips] to having an STI can increase our [tooltips content=”The amount of a virus in our bodies, most often measured in the blood. In More Than Sex, when we talk about viral load we mean the amount of HIV in the blood of someone living with HIV.”]viral load[/tooltips] Increased viral load makes it easier to transmit HIV to sexual partners.

For people who do not have HIV: inflammation and sores caused by STIs can make it easier for HIV to enter the [tooltips content=”Part of the body’s circulatory system that transports blood throughout the body.”]bloodstream[/tooltips].

Hepatitis (Hep) A

Hepatitis A, also known as hep A and HAV (Hepatitis A Virus), is a virus that causes liver inflammation.

After a short illness, most people get better on their own without needing treatment.

How is Hepatitis A Transmitted?

Hepatitis A is transmitted by getting feces (poo) with the hep A virus into the mouth.

During sex, hepatitis A can be transmitted when trace amounts of feces get into the mouth from rimming, fingering the anus, fisting, anal sex without condoms, handling sex toys used in someone’s anus, or handling used condoms or other barriers (dental dams, gloves, finger slips) that have been in someone else’s anus.

Hepatitis A is most commonly transmitted when eating food or drinking water that is contaminated with feces. This may happen when a person preparing or handling food does not wash their hands properly, food was not cooked well enough (especially shellfish), or the water (including water used for ice cubes or drink mixes) was not properly treated.

What Are the Symptoms of Hepatitis A?

Symptoms usually develop within two to seven weeks after transmission.

Many people do not experience any symptoms at all, and for others the symptoms can still be very mild. Symptoms may include a general flu-like feeling with loss of appetite, fever, nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting. Symptoms can also include jaundice, when the skin and sometimes whites of the eyes take on a yellow tinge, urine becomes dark-coloured, and feces becomes light in colour. We may also feel a tenderness on the right side below the ribs, where the liver is located. Symptoms might last from two weeks to several months.

How Do We Test for Hepatitis A?

A blood test is used to test for hepatitis A.

Our health care providers may not offer us a hep A test unless we let them know about types of sex that may transmit this virus.

A blood test can confirm the presence of hep A antibodies, and our immune system‘s response to the infection. Usually the health care provider will have two blood tests drawn at once, one to test for hep A itself, and another to test for immunity from receiving the hep A vaccine.

Hepatitis A is an STI that is reportable. If we test positive, public health will work with us to notify our current and recent partners. We can choose to let our partners know ourselves that they may have come in contact with hep A and may want to get tested. The goal of this process is to let our sexual partners know they may have been in contact with hep A so that they can make informed decisions about the sex they’re having, especially if they haven’t been vaccinated for it (more below)..

What Are the Treatment Options for Hepatitis A?

Our body will cure itself of hepatitis A with time. We can help ourselves recover by taking it easy, getting lots of rest, and staying away from hard work and strenuous exercise. It’s important to drink plenty of fluids, and try to avoid alcohol while the liver recovers. It is also recommended to refrain from recreational drugs while recovering.

After we recover from hep A we will be immune to reinfection, meaning that we cannot have hep A again. We can still however acquire the other hepatitis viruses, hepatitis B and C.

How Do We Prevent Transmission?

The most effective prevention is to be vaccinated against hepatitis A. The vaccine is a single injection administered into the upper arm by a healthcare provider.

The vaccine is very effective and can prevent transmission for up to ten years. A blood test can be done to see if we are immune to hep A if we have forgotten or don’t know if we have received it.

The vaccine is free for many community members, including self identified men who have sex with other men, people living with HIV, and people who use drugs. Even if we’re not specifically mentioned in the guidelines, many of us may still be able to access the vaccine for free. Speaking with a health care provider can support us in determining if we’re eligible. Ask about it at a HIM Sexual Health Centre or wherever we are accessing sexual health care.

Avoiding contact between feces and the mouth prevents hep A:

- Use an internal or external condom for anal penetration (including sex toys)

- Consider a dental dam for rimming, a finger slip or glove for fingering, or a glove for fisting.

- Washing our hands before putting finger slips or gloves on and after we take them off helps prevent acquiring hepatitis A.

- If we are not using finger slips or gloves for fingering or fisting, it is important to wash our hands both before and after these activities, and between partners if we are playing with more than one person at once.

Before rimming, try to clean the anus well. Before we put any body part, prosthetic, or sex toy that has been in someone’s anus in our mouth, we can wash it to remove any trace amounts of feces.

Having fewer sexual partners will also reduce the chance of acquiring hepatitis A. HIV-specific hep A, including PrEP, do not reduce the chance of transmitting or acquiring hepatitis A.

Hepatitis A and HIV treatment, PEP & PrEP

Hepatitis A affects the liver and inflammation of the liver can affect how our bodies process medication, including medication used to treat and prevent HIV.

If we are diagnosed with hep A, talking to our health care provider about the medication we are taking will mean we can make any necessary adjustments to avoid side effects.

Hepatitis (Hep) B

Hepatitis B, also known as hep B and HBV (Hepatitis B Virus), is a virus that causes liver inflammation.

Most people who acquire hepatitis B will completely recover without treatment.

Around five percent of people who get hepatitis B will not be able to clear the virus on our own, leading to chronic or long-term hepatitis B. In this case, people may feel well and not have symptoms. However, because hepatitis B remains in the body it can still be transmitted to others. A doctor can help to choose next steps if we develop chronic hepatitis B.

How Is Hepatitis B Transmitted?

Hepatitis B can be transmitted through blood, cum (semen), pre-cum (pre-ejaculate) and frontal/vaginal fluid.

Transmission can occur during anal, frontal/vaginal or oral sex, including rimming without a condom or dental dam, and when sharing sex toys that are not sterilized or covered with a new condom between partners.

Hep B can also be transmitted by sharing injecting drug equipment such as needles and syringes, sharing other drug use equipment such as cocaine straws and crack pipes, being tattooed or getting a piercing with unsterilized needles. Medical and dental procedures with unsterilized equipment, and childbirth can transmit hep B.

How Do We Test for Hepatitis B?

A blood test is used to look for hepatitis B antibodies. If we test positive, we may need a further blood test to determine if the liver has been damaged.

What Do We Do if We Have Hepatitis B?

Many people with acute hepatitis B do not require treatment, and with time our body will cure itself of the infection. We can help our recovery by taking it easy and getting lots of rest, as well as avoiding alcohol and recreational drugs while our liver recovers. Our health care provider will use information from regular blood tests and physical check-ups to make sure our body clears the infection.

After we recover from hepatitis B, we will be immune to reinfection, meaning we cannot have hepatitis B again. We can still however acquire the other hepatitis viruses, hepatitis A and C.

If our body does not clear hepatitis B, we will develop chronic hepatitis B. In this case, there are medications that slow viral reproduction and boost the immune system. However, treatment cannot usually cure chronic hepatitis B. Most people who start treatment will need to continue it for life.

How Do We Prevent Transmission?

The most effective prevention is to be vaccinated against hepatitis B. Depending on where we grew up, we may have been vaccinated for hep B as children. The vaccine is very effective and we can get a blood test to see if we are immune to hep B from vaccination. Rarely, some of us who get the vaccine may need a booster.

Hep B vaccines are provided free to many people in BC. Ask about being vaccinated at a HIM Health Centre, at our doctor’s office, or at our local sexual health clinic .

If we have not had a hep B vaccine, we can reduce the chances of transmission by using a barrier during sex, such as an internal or external condom for anal or frontal/vaginal penetration whether with body parts, prosthetics, or sex toys. Having fewer sexual partners will also reduce the chance of acquiring hepatitis B. HIV-specific prevention strategies, including PrEP, do not reduce transmission of hepatitis B.

Sharing needles and syringes used for injecting drugs, as well as cocaine straws or bank notes for snorting drugs, or pipes for inhaling/smoking crystal meth or crack can transmit hepatitis B. Because hep B can survive for over a week outside of the body, sharing razors, toothbrushes and manicure tools can also transmit this virus. As well, reusing needles during tattoos, body piercings and acupuncture treatment can transmit hepatitis B.

What Are the Symptoms of Hepatitis B?

Many people do not notice any symptoms of hepatitis B.

Symptoms of acute hepatitis B usually develop within four to six weeks after transmission. Symptoms may include a general flu-like feeling with loss of appetite, fever, nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting. Symptoms can also include jaundice, when the skin and possibly whites of the eyes take on a yellow tinge, urine becomes dark-coloured, and feces becomes clay-coloured. We may also feel a tenderness on the right side below the ribs, where the liver is located.

Symptoms of a chronic hepatitis B infection can be similar to those of acute hepatitis B. They tend to be mild to moderate in intensity and come and go over time. It is when someone has chronic hepatitis B that they are at higher risk of liver failure, liver disease and cancer of the liver. Especially because symptoms of these more serious conditions may take years to develop, we may have no idea what is causing them.

Hepatitis B and HIV

If we are living with HIV, a hepatitis B vaccination is especially important. Hep B vaccines are free to people living with HIV in BC. If we acquire hepatitis B, it can impact our HIV health and treatment. We can talk to our HIV health care provider about getting a hep B vaccine, or testing to see if we need a hep B booster.

When someone has both viruses, it is known as HIV/HBV co-infection. If we have both HIV and hepatitis B, we are more likely to develop chronic hepatitis B, and the infection can progress to liver damage more quickly. Our HIV viral load is also likely to increase if we also have hepatitis B.

If we are living with co-infection, we can access ongoing care for both HIV and hep B. This may include regular hepatitis B tests and checks of our liver. Letting our health care provider know about both our HIV and hep B status, and any treatment we are on, prevents accidental impacts on our treatment plan. For example, hepatitis B may interact with our HIV treatment. For those of us who have hepatitis B but not HIV, The response of the immune system to having an STI can also make it easier for HIV to enter our bloodstream for those of us who are HIV-negative.

Hepatitis (Hep) C

Hepatitis C, also known as hep C and HCV (Hepatitis C Virus) is a virus that causes liver inflammation.

There are acute and chronic stages of the disease. 20-25% of people are able to clear the virus on our own during the acute or early stage of infection. However, most people’s bodies will be unable to, leading to chronic hepatitis C.

How Is Hepatitis C Transmitted?

Hepatitis C is transmitted when blood containing the hepatitis C virus gets into the bloodstream. Microscopic traces of blood can carry the virus, and the virus can survive in dried blood outside the body for at least sixteen hours, and up to several days and even weeks.

The most common way that hepatitis C is transmitted is by sharing needles during injection drug use. It is also possible to transmit hepatitis C when sharing cocaine straws or bank notes for snorting, as well as pipes for inhaling/smoking crystal meth or crack, although this is less common than with injection equipment. Using new supplies to use drugs, can reduce our risk of acquiring hep C; we can ask for new harm reduction supplies, such as straws, pipes, and injection supplies through HIM.

Hepatitis C can also be transmitted during some sexual activities..

Hepatitis C is more often transmitted during sex where blood— even small traces— is present. Because the virus can be present and transmitted in even miniscule amounts of blood, amounts that may not be readily visible to the eye, an activity that doesn’t explicitly involve blood play, like rough anal sex, can result in the transmission of hepatitis C. Hepatitis C has also been found in the semen and rectal fluid of some people living with HIV as well as hep C, both for detectable and undetectable viral loads. Hep C in blood or semen on a penis, hand, prosthetic, or sex toy can enter the bloodstream through micro tears in our rectum.

More usually, hepatitis C is thought to be transmitted during group sex where drugs may be present, known as ‘PartynPlay’ (PnP) or ‘chemsex’. Sometimes when people take drugs during group sex situations, we have sex for longer periods than we might otherwise. This can cause the delicate skin lining the anus to tear, providing an entry to the bloodstream for hep C. When several bottoms (persons being anally penetrated) are sharing the same top’s (person penetrating) penis, fists, fingers, or sex toy without using or changing condoms or gloves between bottoms, it is possible that tiny amounts of blood may be transferred from one bottom to another.

Trace amounts of blood may also end up in a communal pot of lube, which can facilitate transmission, especially because the virus can survive extended periods outside of the body. To reduce this risk, we can use a squeeze bottle for lube instead of an open container. Enema equipment that is shared without being sterilized and barriers (condoms and gloves) that are not changed between partners or are handled without washing hands may also facilitate transmission of hepatitis C.

Transmission is also possible from unsterilized tattoo and body-piercing needles, medical and dental equipment that is not new or has not been properly sterilized, sharing razors, nail clippers, or other personal care items that may have blood, including dried blood, on them, as well as from a birthing parent with hepatitis C to their child during pregnancy or childbirth.

How Do We Know if We Have Hepatitis C?